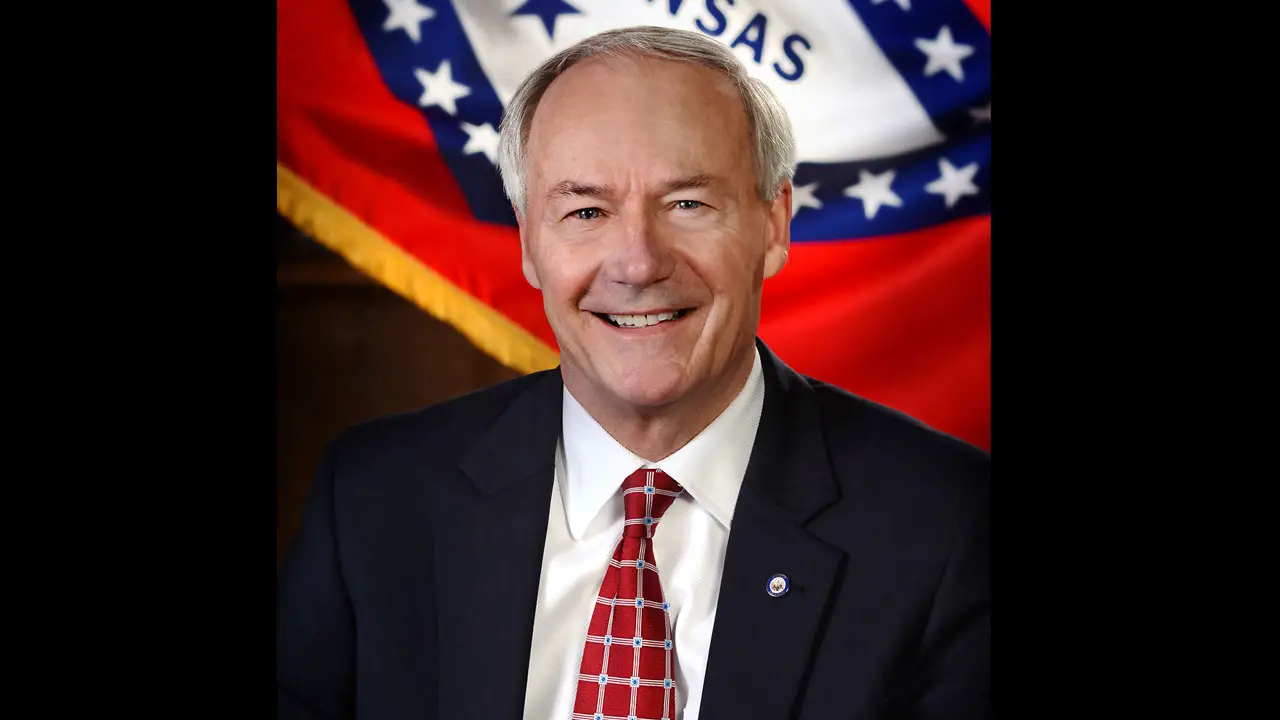

Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson said on Wednesday that he would not sign that state’s “religious freedom” bill that closely mirrors the recently-passed Indiana law that has caused a national uproar.

The key to the decision appears to be pressure from the business community, which has faced calls for boycotts similar to what is happening in Indiana.

Hutchinson, a Republican who just took office three months ago, has been urged by business leaders to reject the RFRA in its current form. Arkansas-based Wal-Mart came out particularly strong against the bill.

“Every day in our stores, we see firsthand the benefits diversity and inclusion have on our associates, customers and communities we serve,” says Wal-Mart CEO Doug McMillan. “It all starts with our core basic belief of respect for the individual. Today’s passage of HB1228 threatens to undermine the spirit of inclusion present throughout the state of Arkansas and does not reflect the values we proudly uphold.”

Hutchinson says that he would like to see changes made to the bill so that it would mirror the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act rather than the Indiana law.

The Indiana RFRA expanded the scope of religion-based civil defenses to include private for-profit businesses. It also provides a civil defense in lawsuits between two private parties, which opponents of the law say will lead to discrimination and the undermine municipal civil rights protections.

A handful of businesses in Indiana have already said that they would deny service to same-sex couples, including a pizzeria in St. Joseph County. Neither Arkansas nor Indiana include sexual orientation in their statewide civil rights laws.

Supporters of the Indiana law say that it is needed to protect religious liberty. They point to the federal RFRA as their model. State representative David Ober even called the law “identical” to the federal RFRA.

However, the laws are not identical.

The federal RFRA, passed in 1993, only covers claims between a person and the federal government. The Supreme Court expanded the definition of “person” in last year’s controversial Hobby Lobby ruling to include “closely held” corporations. Most other state RFRAs followed the same path as the federal law, only applying their provisions to state agencies. Those laws were passed so that governments would not “substantially burden” a person’s religious beliefs unless there was a “compelling interest” on the part of the government.

Opponents of both the Indiana law and the Arkansas bill say that this is a key distinction since they allow for discrimination between private parties based on religious grounds, which is not the case with the federal law or other state RFRAs.